February 21, 2018

By Dr. Bill Romme

You know you’re in the highlands of East Africa when you see Kosso trees. With their rough reddish bark, their long fringed compound leaves, and delicate pink and purple flowers cascading like small fountains from the tree’s crown, Kosso trees have a very distinctive appearance (see Figure 1). But they are not merely easy trees to recognize: Kosso is also one of the most important wild plants for local communities. The wood is an excellent material for carving, furniture building, firewood, or charcoal; the leaves, roots, and bark provide medicines for treating intestinal parasites and other ailments; and the upper branches of Kosso trees are preferred locations for placing traditional bee hives, because Kosso’s nectar makes some of the best honey in the world (see Figure 2). Kosso is also an important wildlife tree: the mountain nyala, a large antelope with elegant curved horns which is found only in Ethiopia, eats the fallen leaves of Kosso and uses the dense forest for cover. Kosso trees can grow to great size, a meter or more in diameter, and probably can live many hundreds of years (see Figure 3).

You know you’re in the highlands of East Africa when you see Kosso trees. With their rough reddish bark, their long fringed compound leaves, and delicate pink and purple flowers cascading like small fountains from the tree’s crown, Kosso trees have a very distinctive appearance (see Figure 1). But they are not merely easy trees to recognize: Kosso is also one of the most important wild plants for local communities. The wood is an excellent material for carving, furniture building, firewood, or charcoal; the leaves, roots, and bark provide medicines for treating intestinal parasites and other ailments; and the upper branches of Kosso trees are preferred locations for placing traditional bee hives, because Kosso’s nectar makes some of the best honey in the world (see Figure 2). Kosso is also an important wildlife tree: the mountain nyala, a large antelope with elegant curved horns which is found only in Ethiopia, eats the fallen leaves of Kosso and uses the dense forest for cover. Kosso trees can grow to great size, a meter or more in diameter, and probably can live many hundreds of years (see Figure 3).

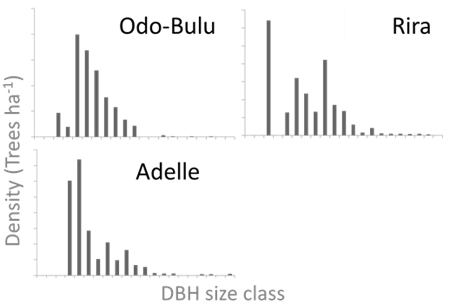

Kosso, also called African redwood, or Heto in the Oromiffa language of southern Ethiopia, is found in high-elevation forests throughout much of East Africa. It is especially prominent in the mountains of Ethiopia, as reflected in its scientific name: Hagenia abyssinica. But a curious thing about this tree: you can easily find large mature individuals if you are looking in the right habitat, but seedlings and small saplings are exceedingly rare, almost nonexistent, in the wild. Kosso is easy to propagate in a garden or plantation setting, and it is sometimes used in groomed landscaping, but it seems unable to reproduce naturally in the wild. In almost every native forest in Ethiopia where Kosso is present, the trees are all or nearly all large, old-appearing individuals. Younger cohorts, i.e., seedlings and saplings (trees with trunk diameters smaller than about 20 cm) are conspicuously missing (see Figure 4). This is worrisome, because as the large, old trees gradually die from natural causes, there are no younger cohorts waiting to replace them. Kosso could eventually decline in abundance, or even disappear from some Ethiopian forests if no regeneration takes place.

Kosso, also called African redwood, or Heto in the Oromiffa language of southern Ethiopia, is found in high-elevation forests throughout much of East Africa. It is especially prominent in the mountains of Ethiopia, as reflected in its scientific name: Hagenia abyssinica. But a curious thing about this tree: you can easily find large mature individuals if you are looking in the right habitat, but seedlings and small saplings are exceedingly rare, almost nonexistent, in the wild. Kosso is easy to propagate in a garden or plantation setting, and it is sometimes used in groomed landscaping, but it seems unable to reproduce naturally in the wild. In almost every native forest in Ethiopia where Kosso is present, the trees are all or nearly all large, old-appearing individuals. Younger cohorts, i.e., seedlings and saplings (trees with trunk diameters smaller than about 20 cm) are conspicuously missing (see Figure 4). This is worrisome, because as the large, old trees gradually die from natural causes, there are no younger cohorts waiting to replace them. Kosso could eventually decline in abundance, or even disappear from some Ethiopian forests if no regeneration takes place.

One of the objectives in our Ethiopian forest research is to understand why those younger cohorts are missing—why Kosso has been unable to reproduce naturally during recent decades. We are testing two principal hypotheses: (i) lack of suitable soil and light conditions for seedlings to thrive, and (ii) excessive browsing on seedlings by livestock and/or wildlife. A combination of these mechanisms may be at play.

Regarding the first hypothesis, Kosso seedlings apparently cannot survive under shady conditions: they need full sunlight to thrive. But in the high-elevation forests where Kosso grows, the tree canopy is typically dense and blocks out much of the incoming sunlight. Adequate light intensity for seedling growth may be available only in places where the forest canopy has been opened up, for example, by a large tree falling and taking smaller trees with it, or where a small fire has killed a small patch of large trees. Lightning almost never ignites a forest fire in the Ethiopian highlands, because lightning is almost always accompanied by heavy rain, but people sometimes accidentally start a small fire. For example, bee-keepers often use smoke to help collect honey from a hive perched high in a tree. A small, accidental fire of this kind might actually aid the Kosso tree's regeneration by creating suitable habitat for the seedlings. Regarding the second hypothesis, we have observed tiny Kosso seedlings in which the upper leaves and buds have been nipped off, and local forest residents have told us that cattle and some wild browsing animals find Kosso appetizing.

Both hypotheses—inadequate habitats for seedlings, and browsing on seedlings--are plausible, and both have a small amount of evidence that would seem to support them. However, our evidence to date is mostly anecdotal and incomplete. We plan to conduct extensive field surveys to more fully characterize the precise kinds of conditions in which Kosso seedlings and saplings can survive and grow into mature trees.  We also plan to conduct experimental tests, for example, by building small fences around Kosso seedlings and saplings to prevent cattle or wildlife from browsing on them, and seeing if the individuals inside the fences grow faster and survive better than the ones outside.

We also plan to conduct experimental tests, for example, by building small fences around Kosso seedlings and saplings to prevent cattle or wildlife from browsing on them, and seeing if the individuals inside the fences grow faster and survive better than the ones outside.

We are working in close association with the staff of the Ethiopian Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change, and with the Gullele Botanic Garden. These agencies have emphasized the importance of Kosso to the ecology of Ethiopian forests and to the well-being of the people living in the highlands. We will post updates as we gain additional information and new insights into the ecological dynamics of the Kosso tree.